Swiss geologist recalls discovering Kerry fossil footprints that rocked the world of science

“This can’t be true. This looks like the traces of a four-legged animal.” So wrote Swiss geology student Iwan Stossel in his field notebook as he sat on a rock in Co Kerry in 1992 after accidentally discovering how life first came to land.

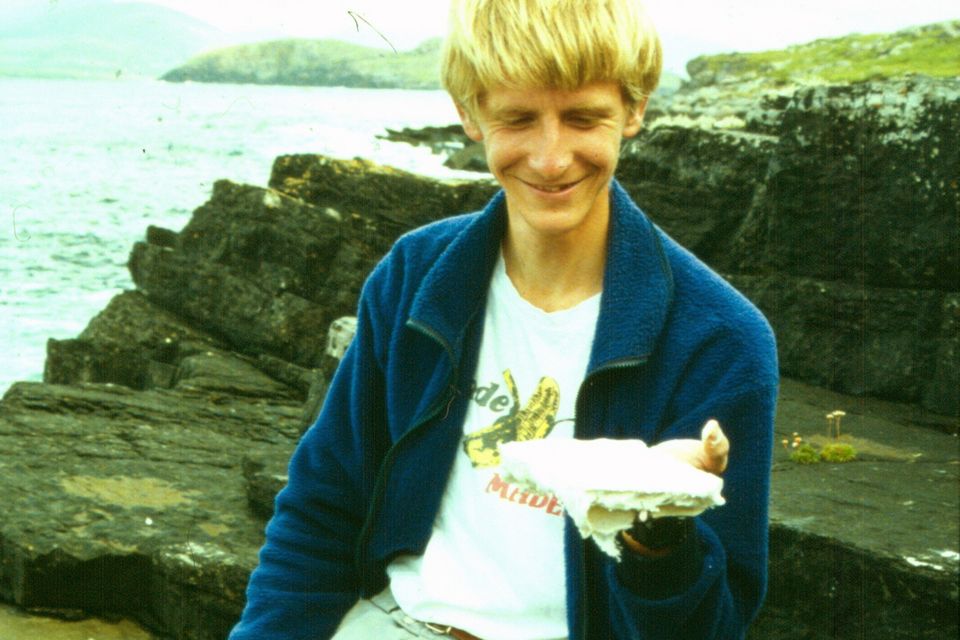

That August, the 23-year-old geologist left his B&B to cycle to Valentia Island, where he was mapping the area’s volcanic geology for his undergraduate diploma.

At a ridge near the shore, he spotted a trail of fossilised footprints in the rock.

The discovery turned out to be the longest set of footprints made by the first four-legged animals ever to walk on Earth and pointed to a key milestone in evolution, when the first amphibians left the water 380 million years ago and walked on to dry land.

The prints belonged to a salamander-type animal the size of a basset hound. It lived when Kerry was semi-arid, long before dinosaurs or humans existed.

Swiss geologist Iwan Stössel made dramatic discoveries in Co Kerry in 1992

It was a discovery that made headlines around the world, but Dr Stossel now says the traces of the footprints were not recognised in scientific literature for a long time.

“Although they were occasionally mentioned in passing, the consequences and implications were not discussed,” he said.

“I assume this was because they contradicted the prevailing view at the time, that tetrapods were only really able to advance to the mainland much later. I was not a vertebrate palaeontologist and, as a practical geologist, no longer part of the academic community.”

He added that he was not able to attend scientific meetings and “defend the case” in discussions with experts.

The story of the discovery will be told on Tuesday in a BBC World Service documentary called Finding the longest set of footprints left by the first vertebrate.

In the Witness History programme, Dr Stossel recalls the day he made the discovery, saying: “You could recognise two sets of imprints separated by a distance of some 30 centimetres.”

In the end, “something like 150 individual imprints, including belly drag marks and tail rake marks” left by the animal were found.

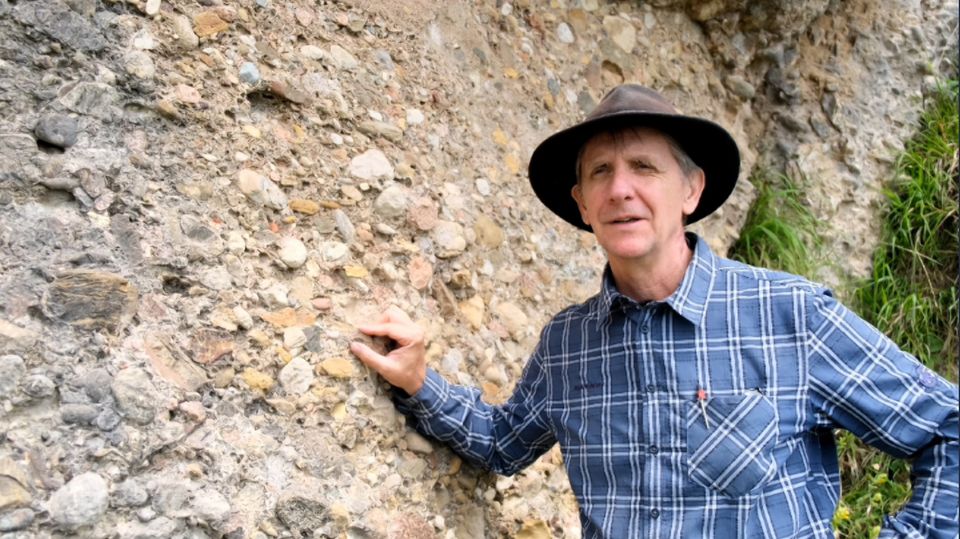

'This can't be true. This looks like the traces of a four-legged animal,' wrote Iwan Stösse after accidentally discovering the track of footprints

Dr Stossel remembers being “very excited”, but “also a bit afraid of the responsibility”.

The documentary notes that no one had ever discovered footprints as old as these from early vertebrates. The find was a sensation because it dates back to long before the arrival of humans and dinosaurs.

At the time, fish made up the majority of living creatures, and Ireland lay south of the equator, with a semi-arid climate that was prone to drought but was not quite desert.

No birds or vertebrate animals lived on the land, but there were spider-like creatures and over-sized scorpions.

“We are talking about a time frame of 380 million years or so, whereas the first dinosaurs evolved around 230 million years ago, so it’s much, much earlier than the dinosaurs. You never get used to these time scales,” Dr Stossel says.

His discovery was a crucial marker in the development of living creatures moving on to land.

“At a certain stage in evolution, vertebrates left the water, and these vertebrate animals are our precursors and also the precursors of dinosaurs,” he says. “These animals are like a very primitive form of salamander-type animal with a tail and a stout body and a broad nose, legs sticking out on either side of the body.

“They probably lived on the riverbanks. They probably also lived in the rivers, but they moved on to the riverbanks and left their traces.”

Theories abound as to why they had to leave the water. One is that they were driven out by predators, while another is that the water became choked with vegetation and had a very low oxygen content.

“I could imagine it is a combination of both,” Dr Stossel says in the documentary.

The footprints contradicted the view of the scientific world at that time, he adds, saying: “It took me some 20 years to install it in the scientific literature. That was a bit frustrating sometimes.”

An even older set of vertebrate tracks discovered in Poland in 2010 added credibility to Dr Stossel’s findings and conferred overdue recognition on him.

“The evolution of the human body goes back to the fish or even beyond that. We still have elements of our fish ancestors within us,” he says.

“And of course, this transition from water to land is one of the key events in evolution, which leads in the end to the human body.

“This explains why there is so much interest in this evolutionary step. But the picture is still evolving. There is still plenty to find — just keep your eyes open and never believe the traditional view.”

The Witness History episode ‘Finding the longest set of footprints left by the first vertebrate’ is on BBC World Service on Tuesday at 8.50am

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news