Editorial: Trinity College Dublin students and authorities sort out differences over pro-Palestine protest

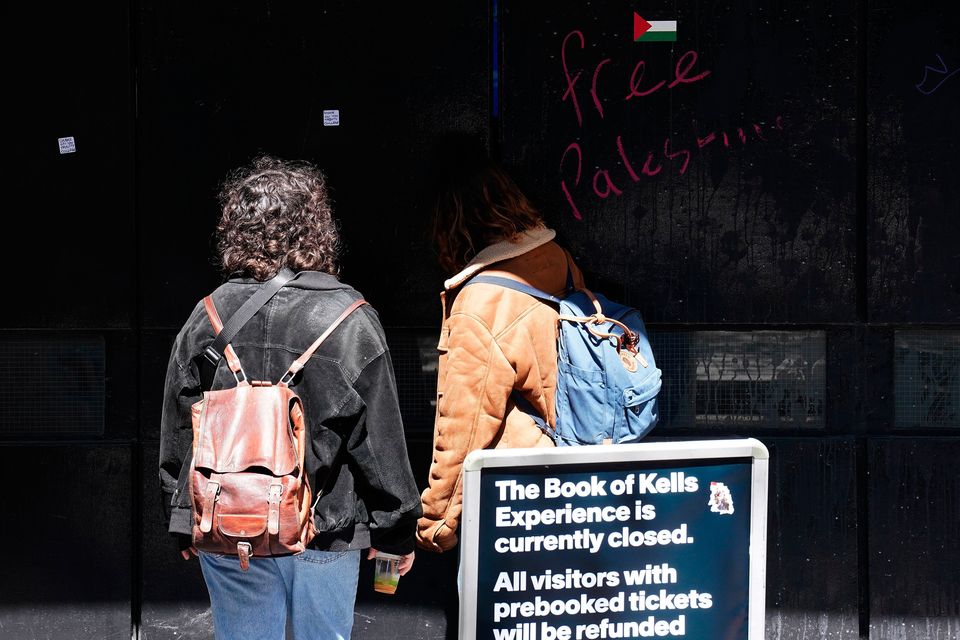

Pro-Palestine slogans on a gate at an entrance to Trinity College, Dublin yesterday. The campus remains closed to the public due to an ongoing pro-Palestinian encampment on its grounds. Photo: Brian Lawless/PA

Peaceful protest against authority has a long and important history in this country. Most famously, the boycott was popularised by Charles Stewart Parnell during the Irish land agitation of 1880 to protest against high rents and land evictions.

The term “boycott” was coined after tenants followed Parnell’s suggested code of conduct and effectively ostracised a British estate manager, Charles Cunningham Boycott. A phrase was born.

A boycott of sorts is now taking place in Trinity College Dublin. TCD students are blockading the Book of Kells, based in the college’s Old Library. Ireland’s oldest university is home to the world-famous ninth-century manuscript, which provides a significant stream of income for the college. Indeed, the gag from detractors of Trinity’s status as a tourist attraction has often been that it conducts lectures for students during the tourist off-season.

Those parallel lines have crossed this past weekend with the Book of Kells blockade. The students have set up an encampment in the city centre Dublin university’s square, to demand that TCD cut ties with Israel because of its war in Gaza.

Outside the college grounds, protests have also taken place in support of the students’ stance. The campus protest has echoed events in the United States where a slew of universities have been plunged into disarray by students mounting protests over the war.

It’s debatable whether this is really a modern-day repeat of the protests against the Vietnam War during the 1970s – an era when student protest became a real driver of social change.

And some of the actions of the US students now have been far from admirable. Accusations of antisemitism against Jewish students and academics are being voiced, reflecting the complexities of the current conflict. A generation so often accused of being apathetic and overly obsessed with image has found a cause to believe in.

In Trinity, tensions had been rising between the college authorities and student body in recent times.

The previous protests targeting the Book of Kells were around increases in the master’s fees and caused a fall in the college’s ticket sales. Hitting the college where it hurt clearly struck a raw nerve. But imposing a €214,000 fine on the students’ representative body was hardly the most mature response.

Protesting is part of the raison d’etre of a students’ union, after all. As Mahatma Gandhi put it: “You may never know what results come of your actions, but if you do nothing, there will be no results.”

The students are aligning their current actions with the campaign against apartheid in South Africa.

Trinity College says it respects the strong stance expressed by the people participating in the encampment protest and blockade, and support the right to peaceful protest.

College and students alike would be well advised to dial down the rhetoric and engage in talks to resolve their differences.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news